Why I’m not a centrist

Back in 2017, I finally realized I had to pick a side. This is the story of how it happened.

I. DISCRETION

One day in August 2017, in the eighth month of the current American crisis, as the Democratic party split itself angrily in half and the Republican party wavered between ill-disguised incompetence and full-on malevolence, I stumbled on an article in Politico that suggested all was not lost:

13 independent candidates who feel they don’t fit in the Republican Party in the age of [the president] are joining forces with a few registered Democrats, all looking at runs for governor and Senate in 2018. The plan is to create shared infrastructure and funding for a slate of campaigns around the country, in the hopes of making this more than the latest go-nowhere whining about how awful the two-party system is.

This new independent political venture was anything but quixotic, the story suggested. It was founded by the economist Charles Wheelan, staffed by an impressive roster of political operatives from both major parties, publicly supported by Evan McMullin and counseled by strategist from Emmanuel Macron’s “En Marche!” party. It was funded to the tune of three-quarters of a million bucks, and that was without any particular public fundraising effort. It was called the Centrist Project, and I was in.

By its own account, the Centrist Project was “a grassroots movement of Americans — Democrats, Republicans, and independents — who feel left behind by both parties and who want our leaders to work together to get things done … We are giving the silent majority a voice on some of the most important public policy issues of our time.”

The Centrists were not wishy-washy, they said. They had principles, and they were principles I believed in. Centrists believed in putting country before party; in following the facts; in finding common ground. They didn’t want to be third-party spoilers—instead, their “fulcrum strategy” aimed to recruit and run independent candidates in carefully selected state legislatures, and the U.S. Senate, to force commonsensical policy compromises between Democrats and Republicans. (Having seen how just three Senate Republicans saved the nation from a health-policy disaster, I found this strategy all the more compelling.)

After ten minutes on the Centrist Project website, I joined as a “founding member.” I felt as though I’d found a political home.

There was no Twin Cities chapter of the Centrists yet, so I volunteered to start one. I made a Meetup group and a Facebook group and wrote enthusiastic messages to people who expressed interest. I started tweeting Centrist stuff. I joined the Project’s monthly leadership conference calls and took careful notes. I was all in.

The national outreach director was delighted to have a new chapter. “What do I do next?” I asked. He had great ideas: How about holding some public events to recruit new members? How about writing a letter to the editor to talk about my conversion to Centrist politics, and offering a Centrist perspective on Minnesota politics? Great ideas! I said, nodding. I’d definitely consider them.

Meanwhile, I went about being a Centrist … discreetly.

I donated money to the Centrist Project monthly, and to Centrist-endorsed candidates like the excellent Terry Hayes, who was running for governor in Maine. But I didn’t encourage anybody else to do likewise.

I met with people one on one to talk over discuss Centrist ideas. When they asked me what they could do to help get the Centrist Project up and running in the Twin Cities, I said “Nothing yet! I’ll be in touch.”

On Centrist leadership calls every month, I’d hear about the public events that other chapters were organizing: a whiskey-tasting to help educate voters about ranked-choice voting; a volunteer effort to help feed the hungry; a big sign at a popular intersection. I read my fellow Centrists’ op-eds and was impressed by them, and dutifully tweeted them out.

Every few days, I’d start to write my own op-ed about “Why I’m a Centrist, and Why You Might Be Too.” But I never got beyond the title. I couldn’t quite commit myself to being Centrist in public, and I was didn’t know why.

Then some things happened.

II. The power of structural politics

![By Anthony Crider (Charlottesville “Unite the Right” Rally) [CC BY 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/53e4d517e4b0dc6847406585/1583943083254-TZK27IHAR5VT70SVWR3O/image-asset.jpeg)

Charlottesville happened, for instance, and the president of the United States deliberately and repeatedly gave aid and comfort to white supremacists. Graham-Cassidy almost wrecked the health system. Roy Moore, who honestly believes that the Bible is the law of the land, won his Alabama senate primary. I could go on.

I responded to these events not in a centrist way, by thinking about the structures of American politics and the processes that uphold our democracy.

Instead, I responded with rage and sorrow—not for the sake of the Republic, but for my own sake, and for the sake of the people I love.

That was how I learned I’m not a centrist after all.

At its best, centrism is a structural enterprise. It’s about the underlying shapes of things: the mechanics of elections and voting, the boundaries of wards and districts, the balance of power in legislatures, the deep grammar of our nation’s political life. Centrism is not about the nitty-gritty of policy positions; reasonable people may disagree about policy, and centrists are reasonable.

This focus on process and form is the power and promise of the Centrist Project, and I still think it matters. But that very structuralism, as powerful as it is, makes centrism impossible for me — in three specific ways.

1. Centrism is principled

First, centrist structuralism enforces a kind of grown-up seriousness that attracts goodwill and maturity, and modest but steady contributions of time and money. The wild-eyed partizans, tinfoil-hatters and true believers who populate the avant-garde of every kind of politics need ideas to get het up about. It is almost impossible to holler about ideas like ranked-choice voting and redistricting. Without specific policy positions, the Centrist Project gives passionate intensity no hooks to hang on. What reasonable person argues against centrist principles of good government, transparency and integrity, tolerance and goodwill, data-driven and human-centered policymaking, and the fundamental excellence of compromise for the greater good? I believe in these principles with all my heart, and everyone I respect does too.

But the people I respect also have convictions about good and evil that make compromise impossible — and, as I’ve been discovering, so do I.

I have friends who would rather stay home than vote for a pro-choice candidate; abortion is a red line for them. Turns out I have my red lines, too: questions of ethics that feel to me so deeply important that I simply refuse to compromise. Turns out that I am utterly intolerant of violence against women and children, whether in the form of outright sexual assault or ill-intentioned healthcare policy, and that I refuse to make common cause with anyone who tries to excuse or wave away such violence. Turns out that I am utterly intolerant of racism, whether with torches or with dog-whistles, and I have no patience for anyone who argues that it can ever be tolerated in public life.

The deepest centrist principles are structural; my deepest principles, turns out, are not.

2. Centrism is smart

Centrist structuralism is really smart, since it’s focused on internal causes rather than external effects. As the centrist story goes, Democrats and Republicans focus on political appearances, while centrists can pierce the veil of partisan illusion to see the deeper causes of policy decisions.

But the unmasking quality of Centrist thought does have a certain … smugness in it, as Andrew Leber argues. The Centrist Project’s deliberate messaging strategy — about the pernicious “duopoly,” about the need to “break through politics,” about “common sense”— strongly implies that everybody who’s in the two parties has just been too foolish, or too obstinate, or too blinded by tribalism, to see the deeper reality that centrists are intelligently pointing out.

To some, that smugness might feel like a problem; to the Centrist Project, that’s a core part of the value proposition. This is troublesome — not least because it invites the charge, leveled with heartfelt fury by Hamilton Nolan, of claiming to be the only “Reasonable Ones” in a nation of partisan hacks.

Yet it turns out that some of the people I admire most in the world—people who are most politically engaged, most principled, most energetic—are “partisan hacks” themselves. I admire my partisan friends too much to suggest, even for a second, that their years of political struggle have accomplished nothing.

3. Centrism is safe

Third, centrist structuralism doesn’t commit us to anything in particular, policywise. As a grown-up homosexual, I find the discretion of structuralism both comforting and familiar.

Those who hate me for my sexuality — like the very fine people who were chanting “Fuck you, f*ggots!” in Charlottesville, for instance — hate the fact of what I get up to with other men. That’s one reason marriage has changed my life: sexuality is content and can be objectionable, but marriage is form and transcends controversy. Form is not disgusting; form doesn’t enrage people. Form doesn’t get you beaten up or killed.

This is precisely why, to my shame, I’ve always taken refuge in ways of thinking that don’t commit me to particular positions. For me, structuralist discretion has been a convenient alibi for mere cowardice.

Once I told a friend that I’d never really “come out” to anyone. He was surprised, even shocked. “Then how do people find out you’re gay?” I explained that I tended to let the topic arise on its own, and then let people their own inferences; I didn’t see any reason to force people into awkward conversations, I said reasonably.

My friend paused a long while before he replied: “That’s fair. But you’re telling me you’re content to let other people have those awkward conversations for you. It’s fine if you don’t want to do the work that comes with being in a minority group, but you should be honest about why you’re unwilling to do it.”

III. A grassroots movement of nobody in particular

Looking back, I think I responded so quickly and powerfully to the Centrist Project because it seemed to promise a way to take helpful, public political action that wouldn’t commit me to any position that might offend anyone.

Who could argue with the minimal policy platform, of good government and (undefined) fiscal responsibility and (unspecified) tolerance and (normless) fact-following data-drivenness? Who could object to the notion that violent partisanship on policy grounds is baleful, and that sincere conversation among grown-up people could gradually, day by day, repair the damaged infrastructure of our democratic process?

I still believe in such ideas; I really do. And yet!

One last Centrist Project leadership call made up my mind.

One of our local chapter organizers had asked for publicly available voter rolls from his state election office, and he was asking how to use the voter information on the lists to target recruiting mailers or phone calls. What had the Centrist Project learned about who, demographically, would be most receptive to our message about “breakthrough politics”? The outreach director of the Centrist Project — a principled guy, a person of integrity and tireless political energy, whom I truly admired — hesitated before he answered the question.

He really, really wished this weren’t the case, he said, but all the data they’d gathered so far had shown that the people most receptive to the Centrist Project tend to be older, and male. And white.

“I have no idea why that’s the case,” said the outreach director, “and I really want our message to resonate with a much more diverse set of people. But that’s where we are.”

Our outreach director might not have understood why the Centrist Project skews older, and male, and white, but I do.

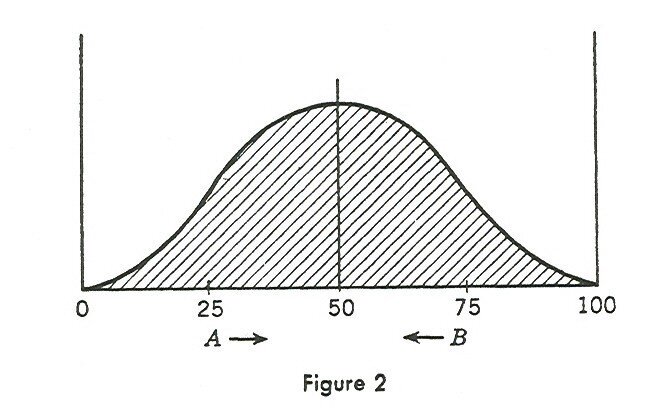

Middle-aged white men are attracted to the Centrist Project because middle-aged white men are the only people in our culture for whom political structures might actually matter more than specific policy positions. They’re the only people who can plausibly claim to be more interested in structure than in content — because they’re the only people in our nation who, by ideological agreement and structural reality, we’ve agreed have no content at all.

At its best, centrism is a structural enterprise, and it appeals to Americans of good will who have the luxury of thinking structurally — the Americans whose demographic characteristics don’t matter at all: straight white men of middle age.

If you’re too old for your parents’ insurance but too young for Medicare—between 26 and 65—you don’t really have an age. By default, structurally, political Americans are middle-aged.

If you’re not a woman, or a trans person, you don’t really have a gender. By default, structurally, political Americans are men.

If you’re not a person of color, you don’t have a color at all. By default, structurally, political Americans are white.

And although our outreach director didn’t specify whether the middle-aged white men who are attracted to the Centrist Project are straight, he didn’t have to. If you’re not bi or queer or somehow odd, you don’t really have sexuality. By default, structurally, political Americans are straight.

“At its best, centrism is a structural enterprise, and it appeals to Americans of good will who have the luxury of thinking structurally — the Americans whose demographic characteristics don’t matter at all: straight white men of middle age.”

These are the assumptions that middle-aged straight white men carry around the world with them. I get this because, in my secret heart, I often want to be one of them — and I almost can be.

IV. Learning to be particular

On days when I wear a suit and tie, I’m almost nobody at all except a featureless unit of default American personhood. With my bald head and tidy goatee, my gender is reassuringly simple. Now that I’ve got a wedding ring on my finger, people can assume I’m married to a woman (as most married men are), so I have no particular sexuality. Everyone who doesn’t know my father is Indian thinks I’m white, and I don’t correct them. I’m too old to be young and too young to be old.

Sometimes, when I catch a glimpse of my reflection in a window during the business day, I think, with a shudder of sociopathy: Wow, I could do whatever the heck I wanted to, and nobody would really stop me. In my suit, on my way to the business factory, I am just some guy, and — reader, forgive me — I dig it.

If you’ve been to college in the past five years or so, you call that feeling privilege. It’s the power that comes with being nobody in particular — the power of transcending any specific identity and moving freely about the world of pure American form, at liberty, without any characteristics that might attract hatred or violence or any strong feelings at all.

My attempt to be a centrist has taught me something important: I’m somebody in particular. And as somebody in particular, I have a side.

I’m somebody in particular because I am not white. In the oddly quaint jargon of white supremacy, I’m what you call a “mongrel.” My father was from India, and my mother is Pennsylvania dutch; they married across racial lines the year after Loving v. Virginia. I’m not white, so I have a side: it’s the side that believes racism is evil.

I’m somebody in particular because I am not straight. I married another man (hi Paddy!) the year after Obergefell v. Hodges. I’m not straight, so I have a side: it’s the side that believes homosexuality is not wrong.

The Supreme Court decisions that legalized my existence and then my marriage have been loudly decried, in some quarters, as the harmful activism of liberal judges run amok; yet I am grateful for them, and I fully expect that, a few decades hence, my marriage will look just as uncontroversial to the next generation as my parents’ did to mine. That belief, and that expectation, give me a side to be on.

The only question is whether I’ll side with my side.

V. The side I’m on

Centrism is premised on the notion that it’s possible to be on the side of good government without choosing sides. Indeed, centrists propose to intervene in the “duopoly” of Republicans and Democrats by insisting that there can and should be a place where reasonable people can convene outside partisan strife.

They are right, I think; and I wish I could meet them there, beyond party, where process and structure matter more than policy and content. But I can’t. I have to side with the party that sides with me, and that means I’m not a centrist. So far as parties go, I’m a Democrat.

I’m a Democrat because the Democrats deliberately side with people who, like me, aren’t white. I’m a Democrat because the Democrats deliberately side with people, like me, who aren’t straight.

So I’m a Democrat, first, for my own sake. But there’s far more at stake in this choosing of sides than self-interest.

Today, America asks us to side with the man with the gun, or to side with the kid in the hoodie. Democrats side with the kid, even if he smokes pot, even if he’s kind of a jerk, because the man with the gun has too much power and the kid in the hoodie, as scary as he may seem, has too little.

America asks us to side with those who condemn the sick to suffer; or to try to bring wellbeing in reach for everyone, no matter what, because all human bodies are fragile. Democrats try to comfort the sick, because we have fragile bodies, and we love other people who do too.

America asks us to side with those who pray loudly in public, or to side with those who try to do what goodness requires. Democrats try to make America the kind of country that does what faith in a benevolent God requires: a nation of peacemakers, where mourners are comforted and those who hunger are fed.

Of course I have my quarrels with the Democrats. Our party is not immune to the blandishments of populist demagogues. Even the most careless Democratic demagogues who truly want the nation to be kinder and more just. I have no love for demagogues; but Democratic demagogues are on the side of the angels, and so am I.

The most wicked Democrat isn’t part of the party that refuses to denounce the man who refused to denounce the Klan. The most careless Democrat isn’t part of the party that simply refuses to debate policy in good faith. The most corrupt Democrat (and there are many) isn’t part of the party that tolerates brazen corruption at the highest levels of government. The most venal Democrat isn’t part of the party that sold its soul for a repeal of the estate tax and betrayed its nation to the schemes of a hostile foreign empire. The most cowardly Democrat isn’t part of the party who takes shelter behind the virile symbolism of the military and the police while innocents, even children, are being tortured abroad and at home.

VI. I’m not a centrist — but you might be

I am a Democrat, at least in how I vote; today, for me, there’s no other way to be American.

But I still think that centrism can be a force for good in politics, and you might be able to.

If you can transcend partisanship, you should. If you can put principles before policy, you should. If you can look past the partisan strife of our moment to care for the wellbeing of our nation for decades and centuries to come, you absolutely should.

Centrism isn’t about embracing the unprincipled middle: it’s about using the power you have to sustain and uphold the democratic structures and republican processes that make civil society possible in the first place. It may be the case that centrists will keep America safe for those of us who, like me, can’t be centrists ourselves. But for now—and as long as I’m somebody in particular—I’ll vote like a Democrat. And I won’t be discreet about it.